Infinite Wheel (Ithildin) Mac OS

Infinite Wheel (Ithildin) Mac OS

But no, since then it doesn't startup in mac os x, bootcamp works fine with windows 7 installed. But starting snow leopard just gives me a grey screen like the safe boot screen with the progress bar and the spinning wheel. The progress bar dissapears after a while and the wheel etternaly spins. You can call it ‘spinning wheel,’ you can call it ‘beach ball,’ you can call it ‘wheel of death’ or any other way you like. The thing is, whatever you name it, the result will be the same – a slower MacBook Pro or Air, iMac or Mac mini. A spinning wait cursor (an official name) can easily drive most of the users mad.

- Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os Catalina

- Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os 11

- Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os X

The spinning pinwheel is a variation of the mouse pointer arrow, used in Apple's macOS to indicate that an application is busy.[1]

Officially, the macOS Human Interface Guidelines refers to it as the spinning wait cursor,[2] but it is also known by other names, including the spinning beach ball[3], the spinning wheel of death[4], the spinning beach ball of death,[5] or the ferris wheel of death.

History[edit]

A wristwatch was the first wait cursor in early versions of the classic Mac OS. Apple's HyperCard first popularized animated cursors, including a black-and-white spinning quartered circle resembling a beach ball. The beach-ball cursor was also adopted to indicate running script code in the HyperTalk-like AppleScript. The cursors could be advanced by repeated HyperTalk invocations of 'set cursor to busy'.

Wait cursors are activated by applications performing lengthy operations. Some versions of the Apple Installer used an animated 'counting hand' cursor. Other applications provided their own theme-appropriate custom cursors, such as a revolving Yin Yang symbol, Fetch's running dog, Retrospect's spinning tape, and Pro Tools' tapping fingers. Apple provided standard interfaces for animating cursors: originally the Cursor Utilities (SpinCursor, RotateCursor)[6] and, in Mac OS 8 and later, the Appearance Manager (SetAnimatedThemeCursor).[7]

From NeXTStep to Mac OS X[edit]

NeXTStep 1.0 used a monochrome icon resembling a spinning magneto-optical disk.[a] Some NeXT computers included an optical drive which was often slower than a magnetic hard drive and so was a common reason for the wait cursor to appear.

When color support was added in NeXTStep 2.0, color versions of all icons were added. The wait cursor was updated to reflect the bright rainbow surface of these removable disks, and that icon remained even when later machines began using hard disk drives as primary storage. Contemporary CD Rom drives were even slower (at 1x, 150 kbit/s).[b]

With the arrival of Mac OS X the wait cursor was often called the 'spinning beach ball' in the press,[8] presumably by authors not knowing its NeXT history or relating it to the hypercard wait cursor.

The two-dimensional appearance was kept essentially unchanged[c] from NeXT to Rhapsody/Mac OS X Server 1.0 which otherwise had a user interface design resembling Mac OS 8/Platinum theme, and through Mac OS X 10.0/Cheetah and Mac OS X 10.1/Puma, which introduced the Aqua user interface theme.

Mac OS X 10.2/Jaguar gave the cursor a glossy rounded 'gumdrop' look in keeping with other OS X interface elements.[9]In OS X 10.10, the entire pinwheel rotates (previously only the overlaying translucent layer moved).With OS X 10.11 El Capitan the spinning wait-cursor's design was updated. It now has less shadowing and has brighter, more solid colors to better match the design of the user interface. The colors also turn with the spinning, not just the texture.

System usage[edit]

In single-tasking operating systems like the original Macintosh operating system, the wait cursor might indicate that the computer was completely unresponsive to user input, or just indicate that response may temporarily be slower than usual due to disk access. This changed in multitasking operating systems such as System Software 5, where it is usually possible to switch to another application and continue to work there. Individual applications could also choose to display the wait cursor during long operations (and these were often able to be cancelled with a keyboard command).

After the transition to Mac OS X (macOS), Apple narrowed the wait cursor meaning. The display of the wait cursor is now controlled only by the operating system, not by the application. This could indicate that the application was in an infinite loop, or just performing a lengthy operation and ignoring events. Each application has an event queue that receives events from the operating system (for example, key presses and mouse button clicks); and if an application takes longer than 2 seconds[10] to process the events in its event queue (regardless of the cause), the operating system displays the wait cursor whenever the cursor hovers over that application's windows.

This is meant to indicate that the application is temporarily unresponsive, a state from which the application should recover. It also may indicate that all or part of the application has entered an unrecoverable state or an infinite loop. During this time the user may be prevented from closing, resizing, or even minimizing the windows of the affected application (although moving the window is still possible in OS X, as well as previously hidden parts of the window being usually redrawn, even when the application is otherwise unresponsive). While one application is unresponsive, typically other applications are usable. File system and network delays are another common cause.

Guidelines, tools and methods for developers[edit]

By default, events (and any actions they initiate) are processed sequentially, which works well when each event involves a trivial amount of processing, the spinning wait cursor appearing until the operation is complete. If processing takes long, the application will appear unresponsive. Developers may prevent this by using separate threads for lengthy processing, allowing the application's main thread to continue responding to external events. However, this greatly increases the application complexity. Another approach is to divide the work into smaller packets and use NSRunLoop or Grand Central Dispatch.

- Bugs in applications can cause them to stop responding to events; for instance, an infinite loop or a deadlock. Applications thus afflicted rarely recover.

- Problems with the virtual memory system—such as slow paging caused by a spun-down hard disk or disk read-errors—will cause the wait cursor to appear across multiple applications, until the hard disk and virtual memory system recover.

Instruments is an application that comes with the Mac OS X Developer Tools. Along with its other functions, it allows the user to monitor and sample applications that are either not responding or performing a lengthy operation. Each time an application does not respond and the spinning wait cursor is activated, Instruments can sample the process to determine which code is causing the application to stop responding. With this information, the developer can rewrite code to avoid the cursor being activated.

Apple's guidelines suggest that developers try to avoid invoking the spinning wait cursor, and suggest other user interface indicators, such as an asynchronous progress indicator.

Alternate names[edit]

The spinning wait cursor is commonly referred to as the (Spinning) x (of Death/Doom).[d] The most common words or phrases x can be replaced with include:

- Disk

- (Beach) Ball[11][12]

- (Rainbow) wheel

- Pinwheel

- Pizza[e]

- Pie

- Marble

- Lollipop

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^NeXT Optical Discs, Photo of the underside, showing the rainbow effect depicted on the icon (a then new type of media that was built into the early NeXT Cubes.)

- ^often an external AppleCD drive was used

- ^not a single bit was changed

- ^named after the Blue Screen of Death

- ^frequently encountered across Mac users forums as The SPOD

References[edit]

- ^'Mini-Tutorial: The dreaded spinning pinwheel; Avoiding unresponsiveness/slow-downs in Mac OS X'. CNet. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 16 July 2012.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^'macOS Human Interface Guidelines: Pointers'. developer.apple.com. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^'Troubleshoot the spinning beach ball'. Macworld. 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^'How to Fix a Spinning Wheel of Death on Mac'. MacPaw. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^'Frozen: How to Force Quit an OS X App Showing a Spinning Beachball of Death – The Mac Observer'. www.macobserver.com. Retrieved 2020-03-22.

- ^'Using the Cursor Utilities (IM: Im)'. Developer.apple.com. Retrieved 2010-04-30.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^'SetAnimatedThemeCursor'. Developer.apple.com. Retrieved 2010-04-30.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Macworld 2002-04-01

- ^Ars Technica Jaguar review: 'The dreading 'spinning rainbow disc' has an all new look in Jaguar'

- ^'WWDC 2012 – Session 709 – What's New in the File System'(PDF). Apple. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

Applications SPOD if they don’t service the event loop for two seconds

CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link) - ^Swain, Gregory E. (28 May 2010). 'Troubleshoot the spinning beach ball'. ((MacWorld)). Retrieved 16 July 2012.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Todd, Charlie (9 March 2012). 'Spinning Beach Ball of Death'. ((Improv Everywhere)). Retrieved 16 July 2012.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

External links[edit]

Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os Catalina

- Apple Human Interface Guidelines: Standard Cursors from Apple's website.

- Perceived Responsiveness: Avoid the Spinning Cursor from Apple's website.

- Troubleshooting the 'Spinning Beach Ball of Death' Excerpt from “Troubleshooting Mac OS X” book where there are some information on how to deal with Spinning Wait Cursor problems.

Officially, it’s called the Spinning Wait Cursor or the Spinning Disc Pointer. Colloquially, it goes by many names, including the Spinning Beach Ball. Whatever you call it, the colorful pinwheel that replaces your mouse cursor is not a welcome sight.

According to Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines, “the spinning wait cursor is displayed automatically by the window server when an application cannot handle all of the events it receives. If an application does not respond for about 2 to 4 seconds, the spinning wait cursor appears.” (WindowServer is the background process that runs the Mac OS X graphical user interface.) Which is to say, the beachball is there to tell you your Mac is too busy with a task to respond normally.

Usually, the pinwheel quickly reverts to the mouse pointer. When it doesn’t go away, it turns into what some call the Spinning Beach Ball of Death (also known as the SBBOD or the Marble of Doom). At times like those, it helps to know why the thing appears and what you can do to make it go away.

Hardware causes

The most basic reason the beach ball appears is because your Mac’s hardware can’t handle the software task at hand. It’s not unusual to see the occasional beach ball when you Mac is performing complex computing tasks. Even everyday activities—such as syncing with iTunes—can temporarily overtax the CPU.

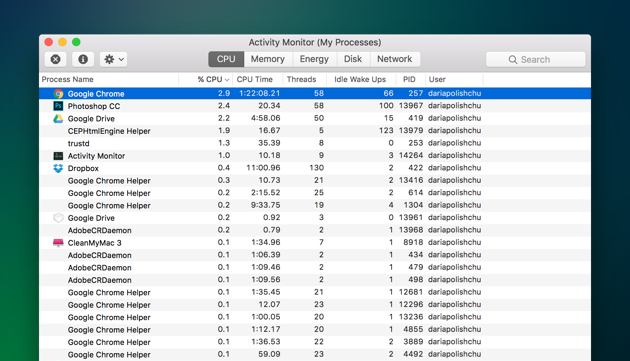

To find out if the CPU is a bottleneck on performance, use Activity Monitor (/Applications/Utilities) to monitor CPU usage. You don’t have to keep an Activity Monitor window open all the time; there are less obtrusive ways to use it. For example, open Activity Monitor then Control-click on its Dock icon and select Dock Icon -> Show CPU Usage. That will turn the icon itself into a CPU usage graph; you can then close the main Activity Monitor window. You can also Control-click on the icon and select Monitors -> CPU Usage, or Monitors -> Floating CPU Window. That will place a small activity graph in the corner of your screen.

The beach ball may also appear if you don’t have enough RAM. Virtual memory paging and swapping (freeing RAM by moving data to swap files on disk and back) consumes CPU cycles. Insufficient RAM means more paging and swapping, which means fewer CPU cycles are available to apps. If apps can’t get the CPU time they want, the beach ball appears. That’s why you want as much RAM as your budget will allow and your Mac can accommodate.

Similarly, if your startup disk is nearly full, less space is available for swap files. Again, that leads to more CPU cycles devoted to swapping and more beach balls. As a rule of thumb, keep at least 10GB free on your startup disk. Again, you can use Activity Monitor to diagnose RAM and hard drive shortages; open the System Memory or Disk Usage tabs. In the pie charts shown in these panes, more green is better.

If you can isolate a hardware cause, the solution is obvious: You need to upgrade. In the case of the CPU, however, that means buying a new Mac. If it’s the RAM or the hard drive, you can upgrade those individually. If upgrading isn’t an option for you, you’re just going to have to run fewer applications concurrently. Clearly, the more resource-intensive apps you work with daily, the fewer you should run simultaneously.

One other hardware-related reason the beach ball may appear: Your hard disk or optical drives may enter Standby mode, spinning down after a period of inactivity to save energy. If you try to access them when they’re in Standby (by opening or saving a file, for example), you may see the beach ball while the disk spins up. For some drives, that may take many seconds.

You can, if you wish, keep your startup disk from ever entering Standby mode. To do so, open Energy Saver preferences (in System Preferences) and deselect Put the Hard Disk(s) to Sleep When Possible. Note that all of your drives will still enter Standby mode when your Mac enters its own sleep mode; you may then see the beach ball if you wake your Mac and then immediately try to access a disk.

Software causes

Even if your hardware is adequate, an application or process can still monopolize your system. Perhaps an application is hung in an infinite loop or it’s simply inefficient. Maybe a background process is running amok, hogging CPU cycles. An errant third-party plug-in can turn a fast application into a slug. Whatever the reason, the program takes over the CPU and up pops the Ball.

If you suspect that the SBBOD is software-based, the first thing to do is simply to wait for a few minutes to see if the app starts responding again or crashes. While you’re waiting, you can find out which apps are hogging more than their fair share of system resources: Open Activity Monitor’s CPU tab and sort by the % CPU column in descending order; the apps at the top are the ones using the most CPU cycles.

If you are able to switch to other applications and the SBBOD appears in all of them, that could be a sign that one of your Mac’s system process is hung. In that case, try to shut down or restart the Mac by pressing Command-Eject or Command-Control-Eject, respectively. Otherwise, press and hold the power button to shut down the Mac, restart, then open the system log in Console (/Applications/Utilities) to see if you can determine the cause.

The SBBOD may also appear when you load a Web page containing a vast amount of data or a JavaScript that is either inefficient or incompatible. Most browsers recognize this situation and open an alert window stating that a script is slowing the browser. Clicking on Stop in this alert should end the problem (though the page may then render incorrectly). Otherwise, you’ll have to Force Quit the browser. If you can, you should report the problem the site’s Webmaster.

Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os 11

Ad-blocking—whether it’s built into your browser or enforced by an add-on—may also cause a browser to hang. In this case, Force Quit the browser, then disable ad-blocking for that particular site.

The Bottom Line

Infinite Wheel (ithildin) Mac Os X

While you can’t prevent every instance of the SBBOD—it is there to tell you your Mac is busy—a little patience and an occasional Force Quit or Restart should make those instances a bit more bearable.

Gregory Swain runs The X Lab, a site dedicated to troubleshooting Mac OS X. He also writes and publishes the Troubleshooting Mac OS X e-book series.

Infinite Wheel (Ithildin) Mac OS